What I Learned From Self-Publishing My Essay Collection

On knowing what you—and your work—truly desire

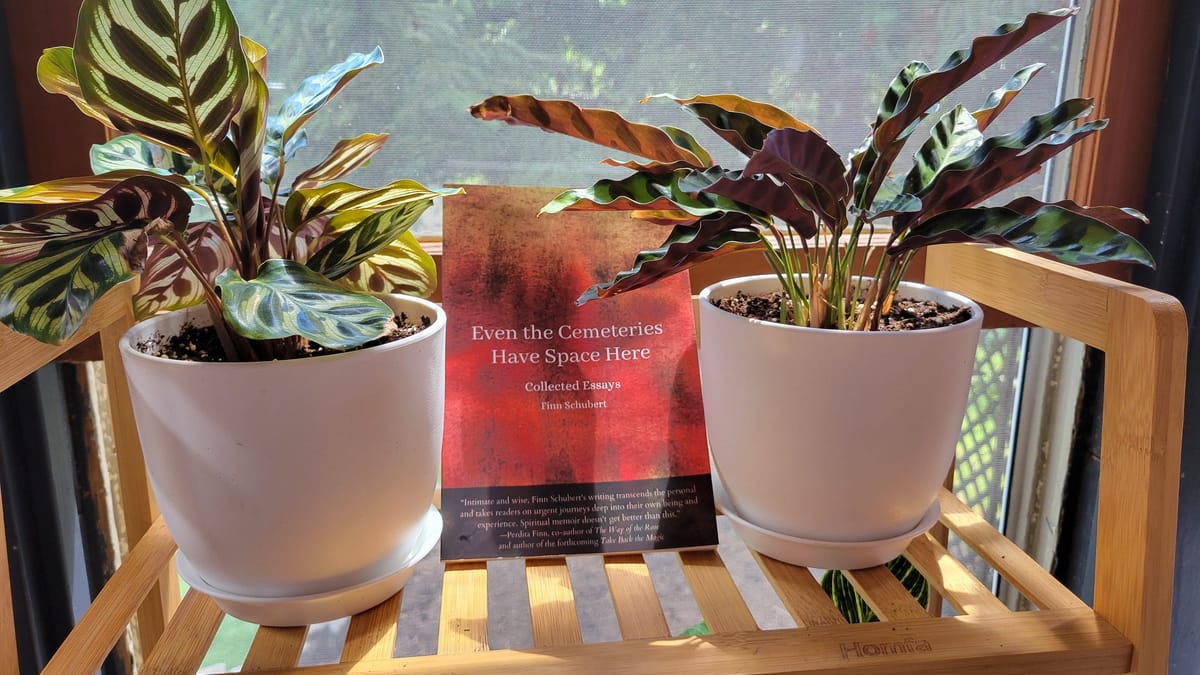

As I prepare to close sales on Even the Cemeteries Have Space Here, I wrote this piece reflecting on what I learned from the process of bringing this collection into the world.

It feels like only yesterday that I announced that I was working on Even the Cemeteries Have Space Here and wrote the essay A Book Is a Spell about my process of beginning to imagine what I wanted the book to be. Now that the current print run is nearly sold out, with no plans to reprint, I am nearing completion of this particular cycle and beginning to think about what I’ve learned from it.

In A Book Is a Spell, I wrote:

Self-publishing this way makes it difficult to get much distribution, it’s not the best option if you want to make money or even get your work into the most hands. But you do get to make every single decision about how your reader encounters your work. Not just title. Not just cover. Font. Spacing. Margins. Paper texture and thickness. Title pages. Everything. You get to make a tangible object that has the ability to set off a transformative experience. In other words, you are casting a spell.

I knew I wanted the reader’s experience of Even the Cemeteries Have Space Here to be spacious and unhurried. The essays in the collection had appeared already on Substack, and although I revised and reworked them for the book, I wanted to offer readers a new experience not through writing new words, but through creating a new way to encounter them.

What Even the Cemeteries Have Space Here offered was a quiet afternoon on the couch with a cup of tea and a book. It offered a book to put on your bedside table to dip into and savor slowly. It offered pages you could flip through until one of the illustrations by Shea in the Catskills caught your eye and invited you in.

I wanted the reader’s experience to be spacious and unhurried—those were my guiding words for the design of the book—and every design decision I made, I used those two words as my guide. When I received the first proof copy of the book by overnight mail in early June, I held it in my hands and knew that it had come out exactly the way I wanted. When readers wrote to me that the book helped them to slow down and reflect, or that their reading experience felt like space unfolding, I felt deep satisfaction that this physical object had carried the original intention across time and space to manifest in their reading experience.

I think it worked in part because I took the time to know exactly what I wanted. I wanted it to be 5 x 7 — and even changed printing companies when the company I’d originally selected didn’t print that exact size. I wanted 1-inch margins and right justification. I wanted a font size neither too large nor too small. I wanted a matte cover, not too thin, and cream or off-white pages. I decided I wanted these things, based on my intention for the reader’s experience, and then I got all of them, and they functioned exactly how I’d hoped. How unusual, how satisfying when things work out that way.

How did I know that I wanted those things? I have to thank Ariel Gore and our fantastic Chapbook Challenge cohort—without Ariel and this class, there would be no book. The first assignment Ariel gave us was to look at books and chapbooks we had at home and write down the specifics about them. How many pages? What kind of binding? How big were the margins? Were there page numbers? A running head? I had never looked at books this way before, and I learned a whole new way to put language to what attracted me to a book and what put me off. I began to understand that a book as a physical object comes from a series of small decisions that form a cohesive whole.

Another invaluable gift from Ariel’s chapbook class was weekly deadlines. The class was designed to get us from concept (with substantial content already written) to printing in just nine weeks. Despite having written a whole essay on finding enoughness as a writer, the prospect of inviting people to pay for my creative work for the first time was terrifying. Would my book ever be “enough” for someone to pay for? Without deadlines, I might have tweaked it forever—adding more work, revising and re-revising, trying to think of any other bell or whistle rather than trusting the offering I was putting forth in order to actually put it out into the world.

Ariel also taught me to take my copyediting to a whole new level. She caught “orphan” lines and awkward line breaks in a near-final layout that I’d looked over completely. The book was okay without those corrections—still entirely readable—but these little fixes made it seamless.

I think it’s important that I came into this process with self-publishing as my original intent. Some writers set out to self-publish, some writers do so only after first trying to publish with established presses. I am interested in traditional publishing for other work in the future, but for this work, I wanted to put it out in the world both quickly and intimately. (It occurs to me now that this is how these essays were written—quickly and intimately—each one written on one particular Saturday over the span of five months, the first ones posted only on Facebook, only for friends. Perhaps this is why I felt that this format was right for them.)

I loved the essays enough to want to give them a home in print, but wasn’t committed enough to this particular body of work to spend years seeking a publisher, then going through the publication process. Knowing what I know now—that this book of essays had infertility grief as a major theme, and that I learned I was pregnant very shortly after the book’s release—I’m even more grateful that the work got into the world before I knew that my own story had taken another turn.

What I was unprepared for was the shipping operation. Some of this, of course, was life circumstances. For the several folks who have written to me for advice on self-publishing, I would definitely recommend that you not publish your book within two weeks of moving to a new place. Your boxes of books and packing materials and stacks of not-yet-mailed orders will mingle with the other boxes of clothes and plates and toiletries that you live out of instead of having furniture yet, while you feel as though you have not just moved and published a book, but rather arrived on a whole new planet where everything takes place in a cardboard box. (Despite this, I would do it the same way again. It was very meaningful to me to send the book to the printer the same day I moved out of the space where it had been written. I wanted it out in the world as soon as I could.)

But if I did it again, I would think more about my shipping infrastructure. How long does it take to ship one book? How many books might I need to ship in a week? When might there be less of a line at the post office? I would have considered all of this in advance and built it into my daily and weekly routine. I hand-addressed all of the envelopes because there didn’t seem to be a click-and-ship option for Media Mail—but I likely could have saved time by printing the addresses.

And then there was Media Mail. Back in January, long before I’d thought anything about chapbook shipping, I mailed a few books to a friend. The lady at the post office said, “Well, Media Mail’s cheapest… but it takes a long time.” She was right. Some books took six weeks to arrive—and in an era of two-day delivery, this just isn’t what we tend to expect anymore. Different post office employees affixed the postage in different ways, and I wondered if each way worked just as well. I received wildly different postage quotes from different post offices branches for the few packages I needed to ship internationally. One book was returned for insufficient postage, while another with the same amount of postage reached its recipient with a few extra stamps, presumably added by some good samaritan postal worker (thank you!) I worried a lot about whether everyone’s book arrived. (Please let me know if yours didn’t — I’ll send you another copy!)

For all these reasons, print-on-demand self-publishing services are sometimes a desirable option. Orders go directly to them, they print your book and ship it out. I explored this option to make Even the Cemeteries Have Space Here available after the initial print run sells out, since it seemed like a way to make the book available over a longer period without having book shipping be part of my routine indefinitely. But none of the services I briefly looked at offered me all of the same exact printing options (sizing, paper weights, etc) that made the book exactly what I wanted it to be.

This body of work has always been intimate and immediate, and I suppose the shipping process was as well—hand-writing each person’s name on their envelope, personalizing each book. I’ve decided I like the idea of closing sales when this print run sells out. Some things are supposed to be for a moment in time, not indefinite.

Self-publishing offered me exactly what I wanted for this particular body of work. I wanted to put it out in the world quickly and intimately, and with great attention to offering a spacious and unhurried reading experience through the design of the book. With another body of work, perhaps I’d want to spend more time revising, working with an editor, perhaps it would be important to me to have it reach more people, even at the expense of giving up some creative control of the final form. I think self-publishing has often been portrayed as a last-resort option for those who couldn’t find a press, but I think it offers its own unique joys, depending on what is right for you and your body of work.

If I’ve learned one thing this year, over the course of putting out my personal essays in my own newsletter and later in my own book, it’s that the most powerful use of my time is writing and putting my work into the world. Shipping my own books was stressful, yes, but maybe not as stressful as writing countless cover letters for lit mag submissions only to receive inscrutable rejection messages three to six months later. Not as stressful as thinking my work wasn’t good enough, rather than that it just hadn’t found the right audience. (In the Witch Shop, one of the more popular posts here, is an older poem that was rejected by lit mags before I learned I could just put out my own work and let it find the people who would resonate with it.)

I am working on a longer manuscript now, one that I do want to sit with for a long time, one that I do want to reach a lot of people—far more than I am reaching currently. This is a different project, and one for which I will seek traditional publication. This will be a new journey for me, with its own joys, I hope, but I know I’ll always treasure the late nights in Phoenicia, surrounded by boxes, Sharpie in hand, writing out the names and addresses of those who were the first to ever pay money for my writing. I wouldn’t have had Even the Cemeteries Have Space Here come into the world any other way.