We Need to Talk About Health "McEquity"

Some practices appear nourishing but offer nothing of substance.

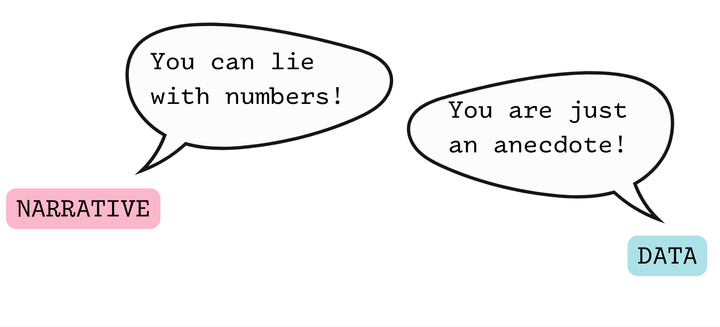

I’m reading McMindfulness by Ronald Purser, which looks at the way that mindfulness practices have been co-opted by neoliberal purposes, encouraging people to address their life challenges through individual self-improvement, rather than through an understanding of social context and collective action. I was particularly interested in Purser’s exploration of the ways in which scientific work is used out of context to bolster these practices.

I couldn’t help but think about public health practice when I read the following quote:

Anything that offers success in our unjust society without trying to change it is not revolutionary — it just helps people cope. However, it could also be making things worse. Instead of encouraging radical action, it says the causes of suffering are disproportionately inside us, not in the political and economic frameworks that shape how we live.

My first post-college job was working for an organization that sought to increase access to abortion and contraceptive training in family medicine. We talked a lot about pregnancy intendedness. About delaying childbearing so that people could complete their education and have greater economic stability.

While of course people need access to contraceptives and abortion, there are also numerous structural solutions to enable people to complete their educations and have greater economic stability regardless of when they choose to bear children.

Off the top of my head, structural interventions like free childcare, universal basic income, and affordable housing come to mind as interventions to support both young parents and everyone else in completing their educational goals and meeting their economic needs.

Yes, yes, these are not achieved overnight, and may not be achievable at all. But by not even putting them on the table as potential solutions, are we narrowing the scope of what might feel possible? Are we narrowing the scope of imaginable solutions?

And are we perpetuating a public health practice in which getting people to adhere to white, heteronormative, middle-class values (in this case: complete your education and marry before having children) is viewed as the best or only way for people to make healthy choices?

From Purser’s McMindfulness, I was introduced to the concept of “disimagination.” Here’s Purser:

We are repeatedly sold the same message: that individual action is the only real way to solve social problems, so we should take responsibility. We are trapped in a neoliberal trance by what the education scholar Henry Giroux calls a “disimagination machine,” because it stifles critical and radical thinking. We are admonished to look inward, and to manage ourselves.

Disimagination impels us to abandon creative ideas about new possibilities. Instead of seeking to dismantle capitalism, or rein in its excesses, we should accept its demands and use self-discipline to be more effective in the market.

The day I graduated from public health school, the dean encouraged us to “take a selfie—no, an inner selfie, a selfie of who you are at this moment.” Sometimes I refer back to that selfie. I think of myself as naive.

It’s embarrassing, now, to admit that it took me so long to see this about public health, a field that arguably was essentially created in order to mitigate the impact of capitalism and economic inequity on the health of the upper classes.

According to a history of the public health system provided in an Institute of Medicine report, the earliest public health efforts involved quarantine, with a particular focus on quarantine of trade ships.

The report continues into the nineteenth century with this quote, which is fascinating in what it leaves out:

With increasing urbanization of the population in the nineteenth century, filthy environmental conditions became common in working class areas, and the spread of disease became rampant.

First, why was there “increasing urbanization” of the population at this time?

Because of land enclosure laws in which land that was formerly held in common for residents of rural villages became “enclosed” (privatized) over the course of the 1700s and 1800s, which caused people to need to leave their villages to seek work opportunities in urban industrial centers. The increasing urbanization was not inevitable but rather in response to changing economic conditions, specifically industrialization and privatization of land.

Next, we learn that “filthy environmental conditions became common in working class areas”—which really means that working people were economically exploited such that they were unable to live in healthy and safe environments.

The report further notes that, “It was simply impossible to isolate crowded slum dwellers or quarantine citizens who could not afford to stop working.” Obviously, this is only “impossible” if one refuses to imagine any sort of collective resourcing. (The reader may wish to draw their own parallels to contemporary issues in public health.)

Back to Purser’s McMindfulness. He writes that the term “McMindfulness” was coined by Miles Neale, a Buddhist teacher and psychotherapist, who described

a feeding frenzy of spiritual practices that provide immediate nutrition but no long-term sustenance.

I think we need to be cautious of something similar happening in health equity.

Over the past fifteen years, I do see a “feeding frenzy” of practices that appear nourishing but provide no long-term impact.

For example:

- Community-based public health programs that are expected by the funder or local health department to roll out “evidence-based interventions” that are wholly inapplicable to the populations served by that particular program

- Funder-required quality improvement projects that require reporting much more quickly than an improvement can be expected to take place

- Cultural competence trainings that have not been evaluated to show an impact on patient experience (and sometimes not evaluated at all)

- An overfocus on “implementing” and “innovating”—adding more and more new programs, with no attention to “de-implementing” those programs that don’t show results

So what’s the alternative?

How can we tell the difference between practices and approaches that genuinely further health equity, vs those that are only “McEquity”?

- We must resist disimagination. We need to put all the potential solutions on the table, no matter how apparently farfetched. These are still important context for the solutions we do choose.

- We must interrogate our theories of change. What are the causal models and assumptions that underpin the approaches we believe to be good ideas? Might these causal models reflect hidden biases or personal values?

- We must create infrastructures for genuine community accountability. Community advisory boards aren’t enough. How can we hold our programs and approaches truly accountable to those we claim to serve?

- We must be open to being wrong. Not every approach is the right approach (at the right time, in the right setting.) While funding pressures create strong incentives to always be right, always be successful, always be meeting our metrics, how can we create space to clearly see when an approach may not be working out?

Health McEquity is easy—do that training, implement that program—but it may not get us to our true vision of health justice.

How can we broaden the scope of our vision for health equity?

We need to think critically, imagine big, and implement small, one step at a time.