Trans People Know Best About Trans Health (Part 1)

Here's a radical thought:

Trans people know best about trans health.

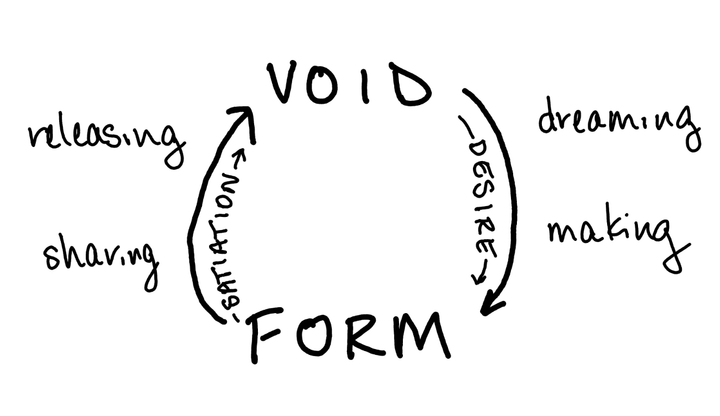

I tend to believe the principle that doctors are experts on bodies in general, and that each person is the expert on their own body, and that the best clinical care is provided at the intersection of this expertise.

Yet we know that this is often not the experience of people seeking care, and that this is disproportionately not the experience of marginalized people, whether it is Black people not being trusted about their level of pain or trans people not being trusted about their lived experiences.

I'm not even primarily talking about the gatekeeping of trans identities, and the legacies of denying hormone care to trans people who didn’t fit stereotypical heterosexist ideas about men and women, such as gay trans men or trans women who didn’t prefer wearing dresses.

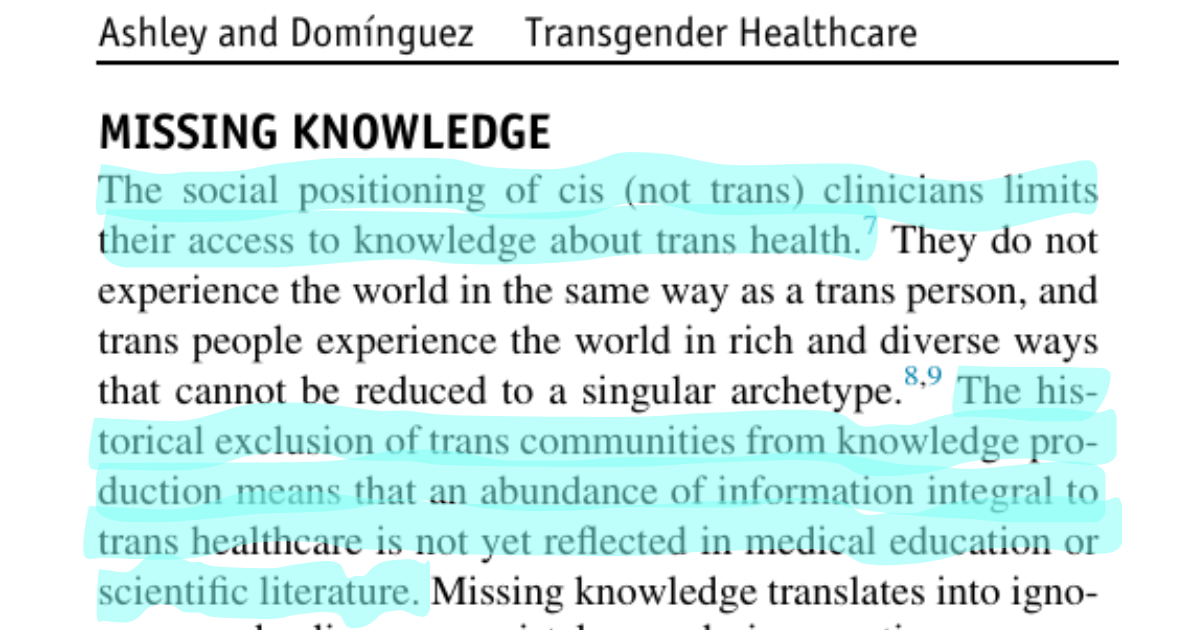

Unfortunately, I am talking about the production of knowledge about trans health.

While we have basic evidence to support the safety and efficacy of gender-affirming hormone therapy (and to refute the disturbing politically motivated lies that threaten to take over the public discourse in this area), there are many questions trans folks reasonably have about our lives that are not well answered by the existing literature.

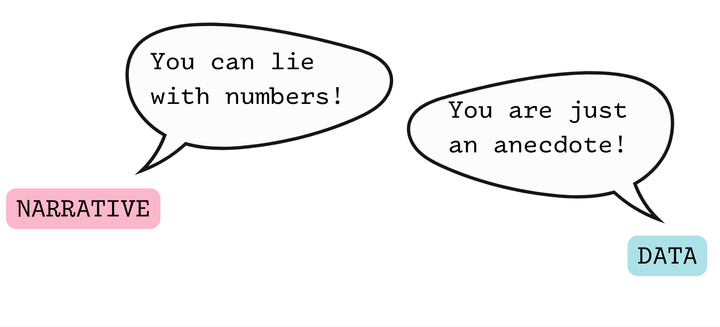

Data on fertility, for example, is inadequate (I wrote about this in AJOG). Various informational handouts are circulated by providers detailing the changes caused by hormone therapy, the length of time it may take these effects to occur, and whether the effects are reversible, yet these often don’t match up with lived experiences or knowledge that community members share with one another.

Community members have often shared informal sources of information, and these informal sources have often been more helpful than the information provided by our physicians.

Rena Yehuda Newman's testosterone survey zine comes to mind, or Mira Bellwether's groundbreaking Fucking Trans Women zine, which offered an overview of trans feminine anatomy, pleasure, and sexual health far beyond what was available from even the most open-minded clinician.

Where we don't have access to traditional empiric knowledge about trans communities, we need to take this community created knowledge seriously.

How can we structure our clinical care to support multidirectional knowledge sharing, where the lived experiences of our patients are actively elicited and used to contextualize and build on more “formal” sources of knowledge about trans experiences?

In approaching research proposals and policy agendas, how can we make sure to include these informal literatures, particularly in shaping research questions that are built around lived experiences rather than a body of evidence largely shaped by cissexist perspectives on trans lives (such as an overfocus on studying “risk,” “disparities,” and “regret”?)

How can we change the way we think about expertise, research methods, and knowledge production to center lived experiences and community knowledge? (This goes far beyond hiring outreach workers “from the community” or having a community advisory board.)

It's time to embrace a broader way of knowing, and to do so will transform healthcare toward justice.