Substack Really, Really Scares Me

Many people say that writers can make more money elsewhere, or even that Substack is actually bad at paid newsletters. But I'll leave that aside because I'm actually concerned about something else. The Substack writers no one talks to for this kind of article.

So, recently Substack raised another $100M in capital, and Ernie Smith explains what's scary about that in a piece called Don’t Call It A Substack. Newsletters Have Been Here For Years. (Not to be confused with Anil Dash's also excellent piece, Don't Call It A Substack.)

Ernie takes us through a fascinating tour of newsletters (remember TinyLetter?) and explains what's so scary about Substack's relationship with venture capital by using an extended metaphor about a piano, which I love:

If you run a company with a seeming growth trajectory, accepting a funding round is like getting an extra hand when playing a piano. When you’re just starting out, maybe you just have one hand to dedicate to playing the melody you’ve chosen. (The other hand is holding up the thing you built so it doesn’t collapse.) It sounds graceful, beautiful, but there’s not much room to create diverse sounds. Plus, your arm’s getting tired from having to do all the work yourself.

You need a second hand, and there are two ways to make it happen: incrementally, as competing platforms like Buttondown and Ghost have done, or by pulling in additional funding, which can let you play a complex melody right away. The problem with that funding is that the hand isn’t actually yours, and they may want to play the melody in a different key.

Ernie writes, "Don't let the middleman shape your newsletter," and reminds us that many of the "network effects" that Substack supposedly has are shadows of things we used to have on the open web, or things we could build more purposefully for ourselves, if we were so inclined:

In the early days of the internet, we found ways to make network effects work without a middleman. Webrings ruled the land. We had guestbooks that people could sign.

But layers of dust started to cover these features, as the desire for ever-increasing revenue changed how we thought about technology. For decades, we’ve been afraid of putting in the extra work to get a great experience, so we default to an okay one.

Sure, Substack has a network. And its network has effects. But there’s no reason, if you run a publishing business, that you actually need it. As users, we keep investing in someone else to solve our problems for us, so we can focus on the thing. I think that’s a real trap.

I think that's a real trap, too. And I feel like that trap is discussed in terms of what Substack means for the "media landscape," which as far as I can tell, means journalists who are trying to figure out how to make a living in the current moment. Apparently the Washington Post is in talks with Substack about using its writers, and Ted Gioia writes that Substack Has Changed in the Last 30 Days.

But Substack is rickety for this purpose, writes Ana Marie Cox. She writes:

It’s the Twitter-to-X pipeline reimagined for writers, with income handcuffs. Those of us who left Twitter when Elon took over did so without leaving money on the table. There was no investment or expectation. With Substack, leaving might mean missing a mortgage payment.

Many people say that writers can make more money elsewhere, or even that Substack is actually bad at paid newsletters.

But I'll leave that aside because I'm actually concerned about something else.

The Substack writers no one talks to for this kind of article.

The person for whom writing was always a dream, for whom sharing their work on Substack and amassing a small list was the first time they felt they might be a real writer.

The parent who doesn't feel they have much time for their writing, but finds time here and there to post on Substack.

The unpublished writer who dreams of a book deal and thinks that growing their Substack newsletter is the only or best way to get there.

I think about these people because I have been all of them, or close enough.

What does it mean to be given easy access to a "platform" for your writing, if it comes with a lack of options to discern what healthy sharing means for you?

What does it mean to turn to a platform for creative self-expression, and be constantly fed subtle (and less subtle) prompts about what that expression ought to look like? To have the words literally put in your mouth: "Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work." The user interface sends a pop-up if it thinks you haven't inserted enough links begging your readers to subscribe.

For a new writer, for someone who is not a journalist or media professional, for someone who started writing on Substack because they always dreamed of writing and it seemed like the way to do it – what does it mean to be at this early stage of writing in public and prevented by design from ascertaining for yourself what it means to share comfortably, what size of audience is right for you (perhaps some size other than, as big as possible!), and what relationship you'd like to have with comments or responses.

And what does it mean when this experience has become so ubiquitous that we forget there are other options for being writers or for sharing our work? What does it mean when we want to be writers, but can't or mostly won't pay $5 or $6 a month (Bear blog, Pika) to not be part of a venture capital wet dream?

The considerations for people who make a living on their writing are different, and have been addressed elsewhere. But there are a lot of people who have little Substacks for other reasons, for whom this platform is shaping what it means to write in public, to share their work, and to engage with others around their writing. Substack is flattening our imagination of what it might mean to write or share work online. And for those, myself included, who had our first taste of writing online for an audience on Substack, this is all the more terrifying because we never knew any other way.

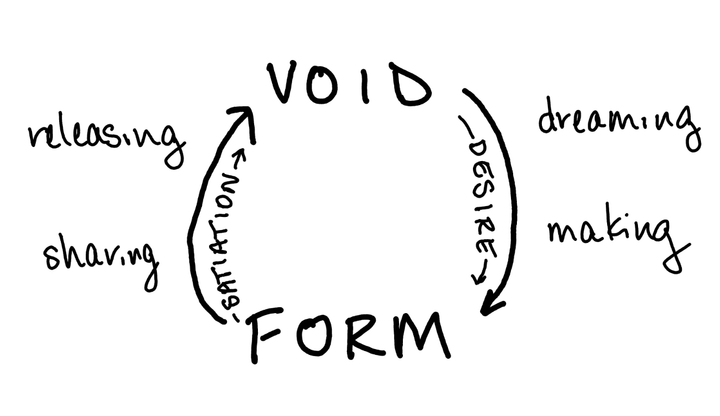

I'm working hard to reimagine what an online sharing practice could look like. Kening Zhu's work has been really helpful with this, as has the practice of taking desires seriously and being rigorously inquisitive around the metaphors I am using to see this situation.

More on why I left Substack:

And on envisioning other ways to share our work:

The feature image on this post is from this mini-zine:

Or see all posts about publishing.

💌 I have a newsletter!

I send emails once or twice a month sharing what's new on my site and some links I've found around.