New tools, new formats, new thoughts

Today I learned how to make slides using Advanced Slides in Obsidian, and how to make diagrams using Mermaid.

Both of these involve making something visual with just text commands. Instead of dragging shapes and text around, in Advanced Slides, you identify where you want it in relation to the edge of the slide, and enter the appropriate numbers. In Mermaid, you use syntax to create a flowchart or other diagram. No more dragging arrows around.

I was curious what would feel possible that didn’t feel possible before.

I’d always thought that making a slide involved dragging text boxes around, resizing them, either writing the text into the slide or copy/pasting it in later. With this other approach, you start with your text and then just divide it into slides with a few keystrokes and add formatting if you want.

I made a complicated diagram in about half an hour that would have taken me several hours to format if I were clicking and dragging.

Will I start to use diagrams more often? Will I make short slide decks and post them online, just for fun?

Things feel possible that didn’t feel possible before. It feels possible to convey ideas differently, which means it feels possible to have ideas I might not have had otherwise.

My book on writing process and diagrams suddenly seems a lot easier to write — and maybe it just wants to be an online slide presentation?

I was reading this article today, about how people learn. Specifically, it was calling out the embedded assumptions in the book format and the lecture format—the idea that just because you tell someone something, they would have learned it.

The author, Andy Matuschak, begins with the observation that he and many others read nonfiction books but are left with only a few sentences of understanding regarding the topic. He seemed to think this was of significant concern.

(I was unconvinced—in addition to the fact that reading and feeling like you’ve learned something can be enjoyable in itself, if you really understand and can use the one or two insights you got from the book, perhaps that’s enough. And perhaps you needed to spend that much time with those core ideas in order to get to that place of fully understanding them. I’m not sure.)

But I was fascinated with what he says about the “grain” of the mediums we use:

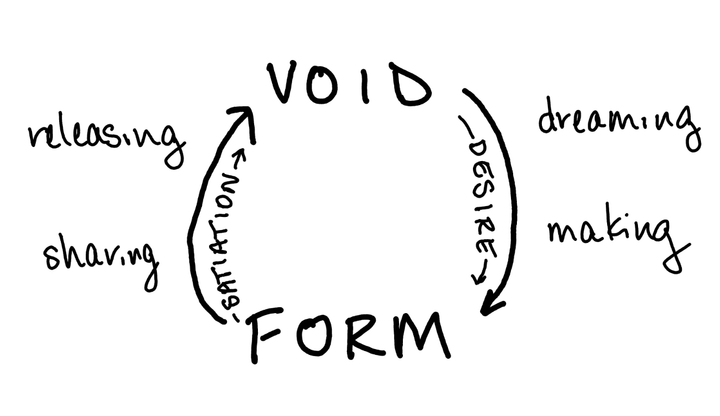

Perhaps most remarkably, the powerful ideas are often invisible: it’s not like we generally think about cognition when we sprinkle a blog post with links. But the people who created the Web were thinking about cognition. They designed its building blocks so that the natural way of reading and writing in this medium would reflect the powerful ideas they had in mind. Shaped intentionally or not, each medium’s fundamental materials and constraints give it a “grain” which make it bend naturally in some directions and not in others.

This “grain” is what drives me when I gripe that books lack a functioning cognitive model. It’s not just that it’s possible to create a medium informed by certain ideas in cognitive science. Rather, it’s possible to weave a medium made out of those ideas, in which a reader’s thoughts and actions are inexorably—perhaps even invisibly—shaped by those ideas. Mathematical proofs, as a medium, don’t just consider ideas about logic; we don’t attach ideas about logic to proofs. The form is made out of ideas about logic.

Matuschak has made an essay that uses the mnemonic medium of spaced repetition as one answer to this:

And so this essay isn’t just a conventional essay, it’s also a new medium, a mnemonic medium which integrates spaced-repetition testing. The medium itself makes memory a choice.

This comes at some cost: you’re committing to future review. But consider what that buys you. This essay will likely take you an hour or two to read. In a conventional essay, you’d forget most of what you learned over the next few weeks, perhaps retaining a handful of ideas. But with spaced-repetition testing built into the medium, a small additional commitment of time means you will remember all the core material of the essay. Doing this won’t be difficult, it will be easier than the initial read. Furthermore, you’ll be able to read other material which builds on these ideas; it will open up an entire world.

I’m surprised at how much time I’m spending on corners of the internet full of programmers. People who take their learning seriously—they solve a coding problem and then post about it. They use spaced repetition. They make linked notes and have a knowledge management system.

I’ve seen hand-coded websites and learned what a static site generator is and encountered people who code their own email and calendar tools so that they don’t have to adapt their thinking to someone else’s tool.

I was fascinated by this! In what ways are our daily digital tools giving us the equivalent of a mental blister, because they’re like an ill-fitting shoe for the way our minds work?

The first thing we have to do to think about whether this is the case is to notice if we’re experiencing friction and to not dismiss it as us being dumb or bad at computers but to wonder—what if this tool was designed around my needs? What are my needs? How might I meet them, short of hand-coding my own tool?

Asking these questions has helped me to find other approaches that have helped me to be more comfortable and generative in my professional and creative work.

So that’s why I was excited to learn these text-based tools for making slides and diagrams. Because maybe I’ll like it better. Maybe it will reduce the friction around expressing myself visually.

Maybe I’ll have a new thought I wouldn’t have had otherwise.