Invoking the Creative Self

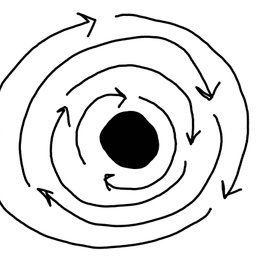

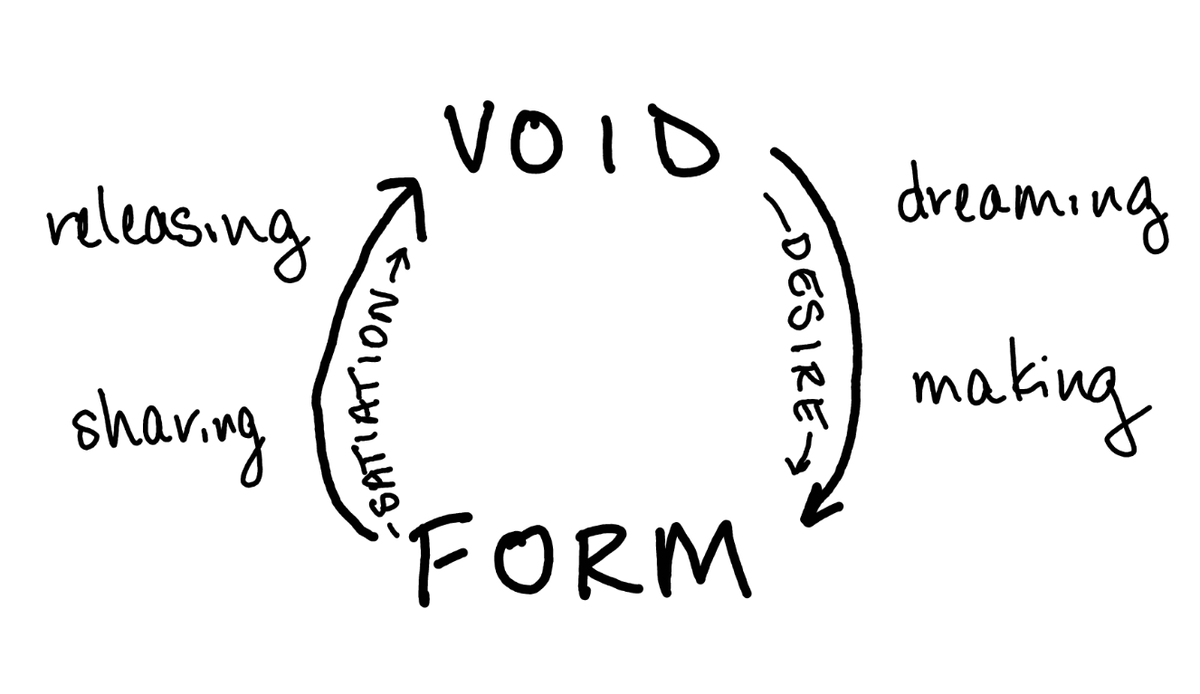

Creative work is always a dance between form and void.

Creative work is always a dance between form and void.

From nothing, we begin with dreaming, then we give form to the imagined reality. It's our desire that propels this process, our desire to encounter that which we imagine. To give it form.

Then the second part is returning to the void. We share our work – maybe in a conventional way, a way described by "likes" or "shares". Maybe in a less conventional way. Maybe we send it to a friend. Maybe we print out one copy. Maybe we do sort of acknowledge it's done and stick it in a drawer, but I do personally feel that sharing with another person is important.

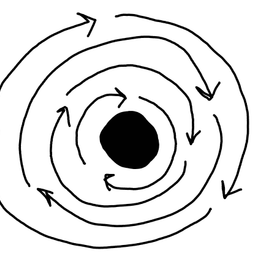

Then we release – the work now has a life of its own.

Just as desire drives the first part of the process, satiation drives the second. We can deepen into our experience of satiation, much as one can roll over and fall into a contented sleep after having sex.

That leaves us back at the void. Ready for new dreams.

It's not that our work no longer has form after we release it. It means we release our attachments or energetic ties to the work's materiality. We allow the work a life of its own.

(If one insists on a birth metaphor, perhaps we cut the umbilical cord. But I dislike birth metaphors as they relate to creative work. I think there are deeper and more universal metaphors available, and that our cultural conception of birth is so warped that it becomes less than useful as a metaphor.)

This cycle feels so opposite from how I used to think of my creative work.

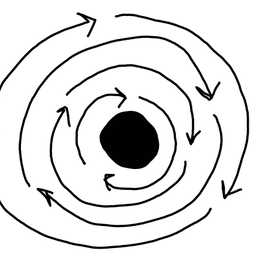

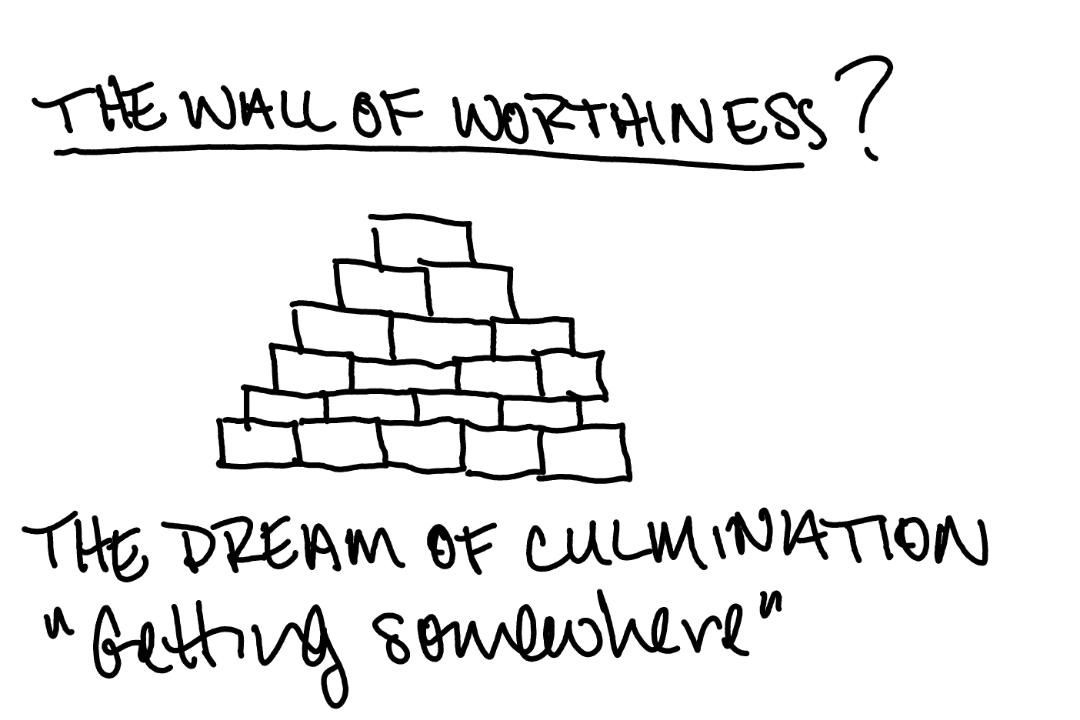

Like stacking bricks, maybe?

As though each finished work was carefully laid down atop the last, as though I were building a wall.

As though I were building a temple to my worthiness. As though that altar - the worthiness, the creative source - didn't already exist within me.

Or maybe it was like climbing a mountain.

The problem with building a wall, is that at the end, you're left with a wall.

Each brick narrows the field of possibilities for what it could become, and for how it could be experienced.

It narrows the field of possibilities for you, and for others.

When we release our work into the void and deepen into satiation, we keep that field of possibility open. Instead of building toward being a "real writer" we can explore moment to moment what we might be becoming. Our spontaneous impulses can flow through us without concern that they might interrupt a rigid plan.

Perhaps you have to give up hope of getting what you thought you wanted, but instead you open the door to something unimaginably more expansive.

In Zen, there are many koans about people not getting what they want.

In a famous story, Emperor Wu is renowned for his support of Buddhism. He studies the sutras and he has made very sizeable donations to support the establishment of monasteries and enable more people to train as monks.

When Bodhidharma, a famous Buddhist teacher, arrives in China, Emperor Wu describes all of this, and asks him, "What merit does this have?"

Bodhidharma replies, "No merit."

In some translations, "None whatsoever."

Emperor Wu then asks, "Who are you, standing before me?"

Bodhidharma replies, "Don't know."

In some translations, "No knowing."

Bodhidharma leaves.

Emperor Wu seems to get a pretty bad rap in the western Zen Buddhism I came up in.

Some versions portray him as venial and selfish, wanting only to be praised.

But – and I say this as someone who has to think about fundraising – he did give a lot of money, and this did allow people to practice Buddhism who could not have done so otherwise.

In some Buddhist stories, a girl who gives a bowl of rice to the Buddha is blessed beyond measure. Many Buddhist texts speak of the supreme importance of realizing the Buddha way for yourself and helping others to do so.

Is it really so bad, then, that Emperor Wu was under the impression that there was some karmic merit to be attached to this?

In some translations, Bodhidharma acknowledges that there is merit, but says that, like a shadow, "it is there, but it is not real."

One scholarly text I read is more understanding toward Emperor Wu, and seems to point out the sincerity of his practice and the social context in which the question might have been asked.

For me, the issue is not that he felt there was merit or wanted to enjoy the sense of there having been merit, but that he felt the need to ask.

When floating in the ocean, there is no need to count the drops.

Related reading