A writing approach I'll never use

I have a confession. Judge if you want.

I have always hated index cards.

I have hated them since fourth grade when we were taught some irritating method of organizing our "bibliography" by tediously writing various information about books in specific places on the index cards. The directive to center the title on the index card was particularly annoying to me and my fourth-grade handwriting.

I know. I know. You probably love index cards. Most writers seem to.

Which is why I've tried them a few other times over the years. I think I tried them once to organize a research paper and another time to organize a novel draft. I still hated them, so I've come up with other approaches to organize my writing that don't feel to me like chewing tinfoil.

And yet, a few years ago, when I found out a writer I admired was teaching a class about how to use index cards to organize longform essays, my lifelong hatred of index cards gave me almost no pause at all. I signed right up! After all, I longed to publish a highly successful book of essays, like hers. And the email announcement for the class came with student testimonials of people who found this method for using index cards completely transformative. Indexing with her method helped one person write the essay that got them into their dream MFA program! Another person used the index cards and got work published in a top-tier magazine!

I happily ordered an index card file box (which I had previously not known were still in production), and several packages of index cards to fill it. My greatest moment of hesitation was when I needed to choose between bold colors or pastels for my index card file dividers.

The class was lovely. The writer did a wonderful job, and I really enjoyed learning more about her process and approach to writing. I cringed inwardly when we were shown a format for transcribing information onto the index cards that reminded me of my tedious and slow fourth-grade handwriting struggles, but we did some exercises with our cards and I saw the benefit of reshuffling them to make new connections between ideas. I left the class feeling excited and eager to start using this new index card superpower to catapult myself to literary stardom.

Friends, to this day, I have never successfully organized an essay using index cards.

Why? Because I have always hated using index cards.

What interests me about this now is that this outcome now seems utterly predictable, and yet, when this writer I admired offered this class, my lifelong hatred of index cards gave me almost no hesitation at all.

I thought: Maybe this is the ticket!

If anything, my hatred of index cards made the idea of a potential reversal and catapult to stardom as a result of this class feel even more compelling.

It seems to me that the reasonable thing for someone who hates index cards to think when offered this opportunity might be: How wonderful that this writer has a flexible method of organizing her ideas that works well for her and that she enjoys! There is no way that I would personally enjoy using index cards for this, but maybe I could think about quirky organizational methods I do enjoy and incorporate them more into my own writing process!

But I was operating under a flawed causal model.

We're all operating under causal models, whether we know it or not.

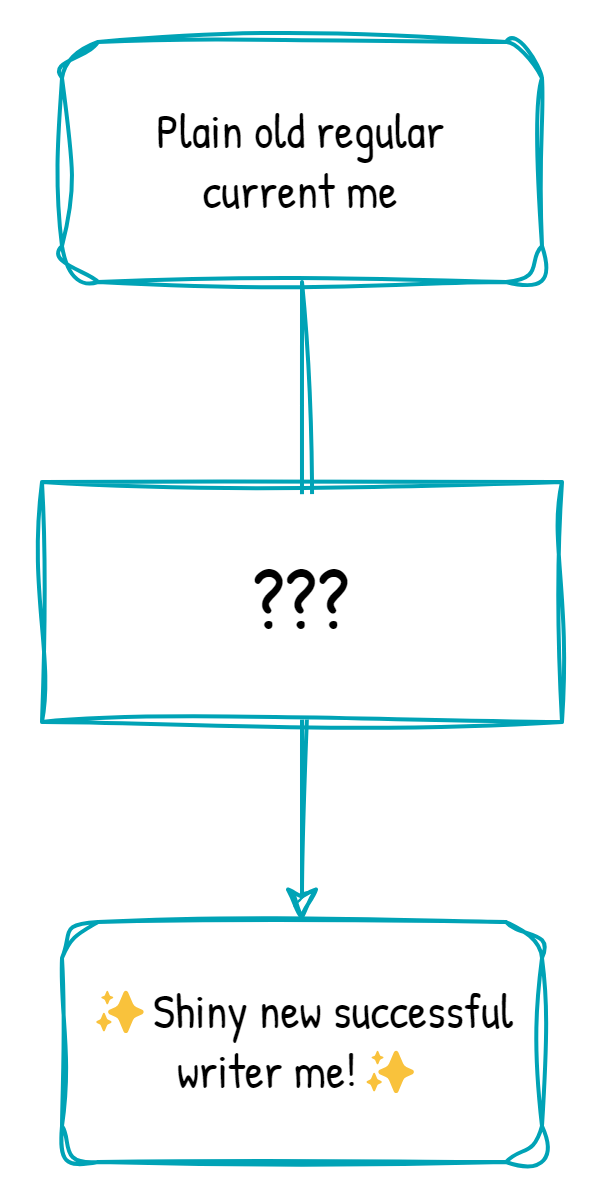

As a new-ish writer, I wanted to figure out the actions I could take that would catapult me to literary stardom. (We'll save for later a discussion about literary stardom and how we define success.)

My causal model could thus be diagrammed like this:

So, how does one find something to put into that middle box? Our thought processes can sometimes be invisible, or sometimes they can rest on assumptions that, if we held them up and looked at them, we might not actually agree with.

When I signed up for the class about index cards, I was operating under the assumption that I should fill the middle box with something that worked for a famous writer, even if it didn't seem like something that was likely to work for me.

Here's a slightly cynical diagram of that thought process:

Well. If I'd drawn that out for myself at the start, I don't think I would have signed up for that class!

But, okay. What do I believe goes in the box instead?

I gave myself a diagram with a blank box, and challenged myself to fill it in.

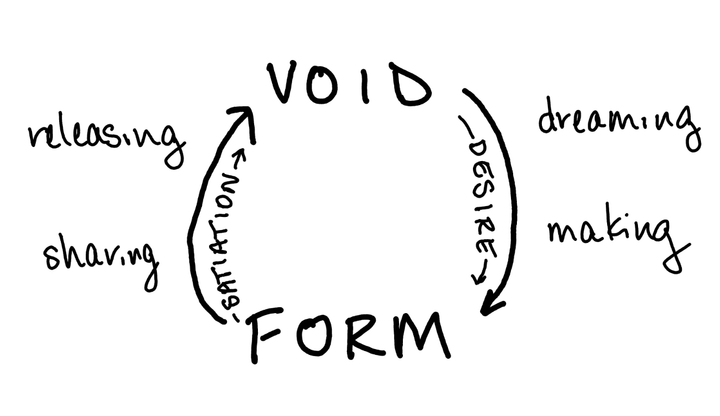

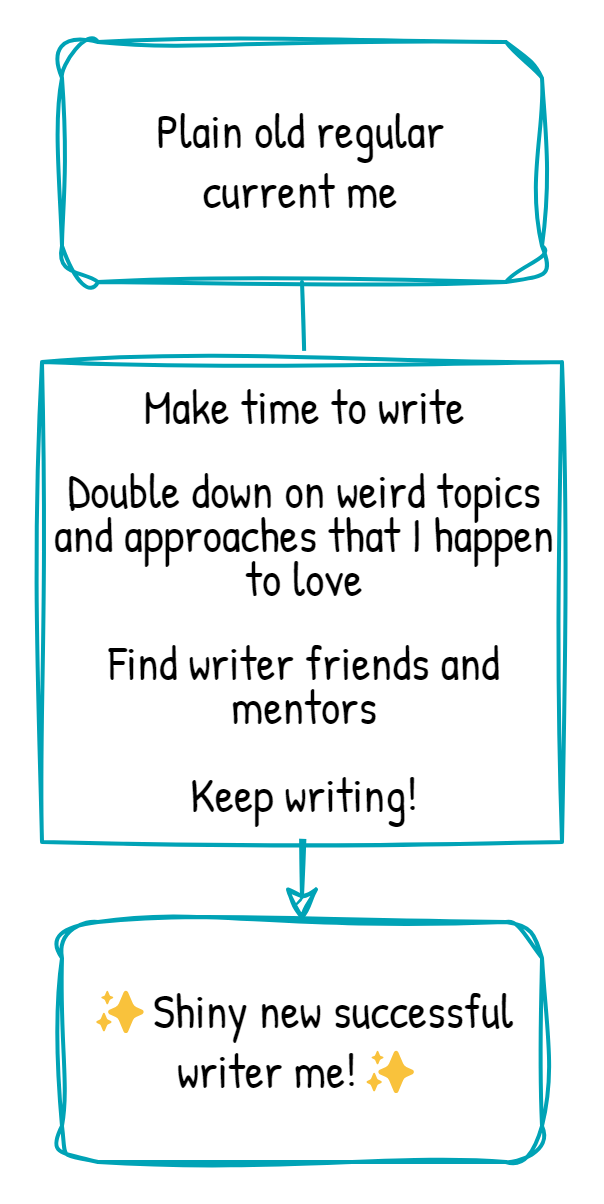

Here's what I came up with:

I mean, none of the things in that box are original or groundbreaking. But they make sense. And now that I've mapped them out, I might be able to better identify which opportunities align with what I actually think will be helpful for me.

The above diagram is a hypothesis, a working model of what I think I should be doing to reach my writing goals. Once I've defined a model--once I've brought my underlying assumptions to the surface--I can test them, and adjust them as needed. But without defining a model, I might be on autopilot, taking classes I don't need and using approaches that just won't work for me.

Maybe later, we'll look at other parts of our subconscious models about what our writing process needs. But sometimes it's a good first step just to bring our existing beliefs to the surface.

What would you put in that middle box?